This Policy Navigator aims to provide a clear and comprehensive approach to exploring the extent to which soil health has been considered in EU strategies, action plans, directives, regulations, and support mechanisms.

The present report comprises the first version of the Policy Navigator and Briefs of the NBSOIL project, whose main goal is to analyse the policy instruments and requirements which directly or indirectly influence soil health at the European level. In other words, this document aims to provide a clear and comprehensive picture of the extent to which soil health has been considered in EU strategies, action plans, directives, regulations, and support mechanisms.

This report begins with a short introduction that highlights the invaluable role played by healthy soils, in terms of their capacity to provide vital ecosystem services and outlines the history of policy attempts made at the EU level to safeguard this natural resource.

The methodology followed to carry out this study is then described. In this regard, academic journal articles have been instrumental in identifying the most relevant policies to examine. However, the most important documents we have consulted and relied on were official EU policy documents.

The European Green Deal is the first broad set of policies that we decided to investigate due to its thematic relevance and strong international reputation. In addition, we have explored the content and the structure of the proposal for a Soil Monitoring Law, the EU Soil Mission, the EU Soil Observatory, a set of policies addressing point source soil pollution (e.g., Environmental Liability Directive, Industrial Emissions Directive etc.) and nonpoint source soil pollution (e.g., Water Framework Directive, Nitrates Directive etc.), the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Directive, the Regulation on the marketing of EU fertilizing products, the Floods Directive, and the Habitats and Birds Directives. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has been analyzed in great detail because of its broad scope, economic importance, and impact on soil health.

Soil is one of the most important natural resources on earth. It provides multiple ecosystem services whose ecological, socio-economic, and cultural values cannot be overstated. Historically, soil has been primarily considered and assessed for its provisioning services since it constitutes the most vital source of food, fibre, wood, and raw materials. This overly simplified understanding of soil functions has often formed the rationale behind policies that ended up incentivizing soil over-exploitation, causing soil impoverishment and degradation. However, scientific evidence has shed light on the many essential ecosystem services provided by a healthy soil. It improves water quality through water regulation, supports climate change mitigation by sequestering and storing large amounts of carbon, advances climate change adaptation by reducing the risk of extreme weather events (e.g. floods and droughts), sustains sustainable plant production through nutrient cycling, provides a habitat for below and above ground biodiversity to thrive, and represents a form of natural and cultural heritage that favours human psychological well-being (EC, 2023a; Lehmann et al, 2020).

Until the publication of the new EU Soil Strategy for 2030 (occurred in 2021), the most comprehensive and ambitious policy instrument to be developed with the aim to advance the protection, sustainable use, and restoration of soil was the Soil Thematic Strategy issued in 2006. For the first time in the history of the European Union, it was claimed that soil had to be regarded as a non-renewable resource and that it was necessary to halt and reverse soil degradation trends by identifying key threats, promoting sustainable management techniques, investing in research, and making national and Community policies compliant with soil protection requirements. The Strategy prompted the European Commission to introduce a proposal for a Directive which set out a framework for the protection of this sui-generis natural resource. The proposal was rejected in 2007 because a group of Member States (MS) maintained that it would not abide by subsidiarity and proportionality principles and that administrative and implementation costs would be too high. It was finally withdrawn in 2014 (Frelih-Larsen and Bowyer, 2022; Heuser, 2022; EC, 2021c).

Despite the Soil Thematic Strategy launched in 2006 was not translated into a binding legislation and failed to bring about any concrete and long-lasting change, it constituted a milestone as it pointed unambiguously out that soil is degrading at an alarming rate and that human activities are exacerbating this issue. The strategy had already identified the following threats to European soils: soil erosion, soil contamination, floods and landslides, decline in soil organic matter, salinization, soil compaction, soil sealing, and soil biodiversity loss.

The direct and indirect environmental and societal benefits stemming from healthy soils, together with the threats faced by this resource, have been largely researched and acknowledged. Nevertheless, the European Union has currently no exhaustive and far-reaching legal instrument to conserve and boost soil health. In contrast to air and water, which have thoroughly been safeguarded by EU Law for a long time through the EU Ambient Air Quality Directives (Directive 2008/50) and the EU Water Framework Directive (Directive 2000/60), soil has been left without a binding legislation (e.g. Directive or Regulation) that would urge/force MS to monitor and assess its status and to conserve it (Heuser and Itey, 2022; Frelih-Larsen and Bowyer, 2022).

Soil protection is currently entrusted to different pieces of environmental legislation adopted by the European Union over the last thirty years. These are directives, regulations, and support mechanisms addressing issues that are directly or indirectly related to soil health, namely industrial pollution, natural habitats, water, waste, biodiversity, fertilizers, and pesticides. The relevance and impact of these policies on soil health will be thoroughly analyse in this report (Heuser, 2022; EC, 2021c).

Furthermore, it will be pivotal to carefully examine the set of policies that constitute the European Green Deal, which was approved in 2020. The latter was conceived and designed to lead the European Union towards climate neutrality by 2050 and to transform it into a just and sustainable society. To achieve these bold and challenging objectives, soil must be fully mainstreamed into European policies. Thus, this report will evaluate to what extent the European Green Deal integrates soil in its roadmap towards sustainable development (Montanarella and Panagos, 2021; Köninger et al, 2022).

One of the policies that will be analysed in greater depth for historical and socio-economic reasons is the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). We have outlined its structure and objectives, as well as its main components concerning soil protection. Furthermore, this report aims to provide an overview of national CAP strategic plans in order to assess whether the measures contained therein can produce positive results on soil health.

Finally, the European Commission submitted in July 2023 a proposal for a Soil Monitoring Law. This report will investigate to what extent this proposal fills the legal vacuum left by European Institutions in this area and whether it can effectively contribute to assessing soil health, promoting sustainable soil management (SSM), and bringing degraded soils back to healthy conditions in EU territories.

The main objective of this policy navigator is to portray the current state of affairs with regard to soil protection and restoration in European Union policies. In other words, this work is meant to provide us with a clear and comprehensive picture of the extent to which EU Strategies, Action Plans, Directives, and Regulations safeguard this invaluable natural resource. Moreover, a further key result of this research is that it will allow us to grasp what soil-related challenges/threats (e.g. soil compaction and soil contamination) have been prioritized and partially addressed, and which ones have been overly neglected.

Two different methods were employed to perform the data collection process.

First of all, EU institutions official websites were explored with the aim to review official Communications, factsheets, law texts, impact assessment reports and policy proposals dealing with at least one dimension of soil health.

Second, Google scholar was the database employed to retrieve relevant academic articles in peer-reviewed journals. Since some of the most noteworthy EU policies have been either issued or revised from 2020 (e.g. European Green Deal, Common Agricultural Policy), scientific papers had to be published in or after that date to fall within the scope of this work; the only exception is for academic articles that investigate technical aspects related to soil health and soil ecosystem services. The following is a non-exhaustive list of key words used on google scholar: soil health, European Policies, European Green Deal, Common Agricultural Policy, soil restoration, EU Regulations and Directives, EU Soil Monitoring Law, Soil protection, Soil degradation, EU Soil Strategy for 2030, Eco-schemes. The research was conducted in English.

In addition, the snowball technique was also adopted. It consists in locating a number of publications through the reference list/bibliography of the academic articles that had been already identified.

Thus, we have conducted an extensive research of academic articles that could provide us with a general overview of the legal status of soil protection in the EU. However, we have also identified several scientific papers which undertake a more analytical and critical study of EU policies in the attempt to appraise their adequacy to tackle soil degradation; these assessments will be particularly useful in the next stages of this work, when it will be necessary to identify policy gaps, highlight potential synergies between policies, and, most importantly, produce recommendations for the mid-term evaluations of the (2025) Soil Mission, the Farm to Fork and EU Biodiversity Strategies, and current CAP (2023-2027).

In December 2019, the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen announced her vision and political priorities for 2019-2024. The EU would aspire to achieve the objectives set out in the Paris Agreement and in the UN Agenda for Sustainable Development in order to become a greener continent and to address those environmental challenges that jeopardize its progress and prosperity, such as climate change, land degradation and biodiversity loss. The European Green Deal (EGD) was conceived as a package of policy initiatives that would promote a holistic understanding of nature conservation and pave the way towards a more sustainable use of natural resources (Heuser and Itey, 2022; Montanarella and Pangos, 2021).

The EU Biodiversity Strategy, the Forest Strategy, the Farm to Fork Strategy, the Zero Pollution Strategy, the Climate Law and the Soil Strategy, constitute the backbone of the EGD and focus, to different degrees, on sustainable soil management and soil protection. Therefore, we will analyse the direct and indirect impact these strategies could have on soil if their measures had to be adopted and properly implemented by MSs.

The EU Biodiversity Strategy (EC, 2020d) recognizes that soil is an essential non-renewable natural resource which is “home to an incredible diversity of organisms that regulate and control key ecosystem services such as soil fertility, nutrient cycling, and climate regulation” (EC, 2020c, p8). In addition, it acknowledges that soil degradation and the desertification looming over some EU regions are accelerated by inadequate land management practices and soil sealing caused by urban sprawling. This situation is further exacerbated by climate change, which has an alarming multiplier effect.

The strategy proposes to protect at least 30 percent of land area under EU law. It also expressly indicates that one-third of protected areas should be strictly protected and that precise conservation goals and strategies should be established to guarantee the correct implementation of these targets.

It promotes the need to maintain at least 10 percent of agricultural area under high-diversity landscape features, which include agricultural terraces, buffer strips, hedges etcetera. Some of the measures that could be adopted by farmers to reach this target would, as a result, reduce soil erosion, improve carbon sequestration, and enhance biodiversity. Finally, curbing soil sealing to diminish human-induced pressure on natural habitats and stepping up the implementation of agroecological practices (e.g. agroforestry), which benefit several dimensions of soil health, are encouraged.

In this regard, it is worth pointing out that at the beginning of November 2023 an agreement was reached between the European Parliament and the European Council on the Nature Restoration Law proposal (Council of the European Union, 2023), which is a key element of the EU Biodiversity Strategy. In the proposal, Art.4 states that MSs should put in place measures, by 2030, to restore at least 30 percent of the habitat types listed in Annex I that are not in good condition and at least 60 percent by 2040 and at least 90 percent by 2050. Especially relevant for soils is Art. 9 on “restoration of agricultural systems”. One of the key targets consists in achieving increasing trend at national level in each of the following indicators in agricultural ecosystems:

(a) grassland butterfly index;

(b) stock of organic carbon in cropland mineral soils;

(c) share of agricultural land with high-diversity landscape features.

In addition, for organic soils in agricultural use constituting drained peatlands, MSs shall put in place restoration measures on at least:

(a) 30 percent of such areas by 2030, of which at least a quarter shall be rewetted;

(b) 40 percent of such areas by 2040, of which at least half shall be rewetted;

(c) 50 percent of such areas by 2050, of which at least half shall be rewetted.

However, the extent of the rewetting of peatland under agricultural use may be reduced to less than required under points (a), (b) and (c) by a MS if such rewetting is likely to have significant negative impacts on infrastructure, buildings, climate adaptation or other public interests and if rewetting cannot take place on other land than agricultural land.

The EU Forest Strategy (EC, 2021b) acknowledges that forest health is inextricably intertwined with soil health. Trees would not grow and prosper if their roots were unable to reach and acquire the most critical nutrients from the soil. For this reason, it states that soil properties and ecosystem services must be safeguarded.

One of the main objectives proposed by this Strategy is to plant at least three billion additional trees by 2030. If achieved, this goal could bring a wide range of positive results in the fight against soil degradation, e.g. reduced soil erosion, increased fertility and biodiversity, and the maintenance of soil structure. In addition, it advocates for more sustainable forest management practices in order to store more carbon in the soil.

The Farm to Fork Strategy (EC, 2020c) sets out a thorough approach to accelerate the transition of the EU towards more just, sustainable, and healthy food systems.

The first and most relevant goal for the scope of this analysis is to cut down the overall use and risk of chemical pesticides by 50 percent and the use of more hazardous pesticides by 50 percent by 2030. The strategy also claims that integrated pest management practices, such as crop rotation and mechanical weeding, will be promoted as safe and alternative methods to cope with pests and diseases. The second one consists in reducing nutrient losses by at least 50 percent and the use of fertilisers by at least 20 percent by 2030.

The excessive and harmful use of pesticides and fertilizers is one of the most critical sources of soil pollution, severely hampering its ability to provide some vital ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration, habitat provision, water purification and nutrient cycling. Its exposure to these toxic substances leads in particular to a loss of biodiversity and organic matter. Therefore, imposing strict limits on their use would undoubtedly curb soil degradation and sustain soil restoration.

Finally, it stresses that the EU would work to expand the reach and market share of organic products through the measures embedded in the Action Plan for the Development of Organic Production (EC, 2021a). The main goal to be attained within the framework of this Action Plan is to have at least 25 percent of the EU’s agricultural land farmed organically by 2030. A wider adoption of organic agricultural practices would further boost soil health throughout Europe.

The EU Action Plan: ‘Towards Zero Pollution for Air, Water and Soil’ (EC, 2021d) highlights the need to adopt an integrated and cross-sectoral approach to prevent pollution and remedy contaminated sites. Its primary objective is to reduce pollution to levels that are not harmful to human health and the environment.

With regard to soil health, the Action Plan intends to limit the amount of pollutants entering into the soil from different socio-economic pathways, e.g. industrial installations, energy sources, agriculture, wastewater, urban infrastructures, transport, and plastics production and consumption.

The strategy promises to enforce EU regulatory frameworks meant to safeguard air and waters and to develop a framework to monitor the status of soils and to tackle their degradation. While this promise is a positive sign of the EU’s commitment to preserving soils, it further demonstrates that soil is the only major natural resource that is not yet protected by legally binding measures.

Furthermore, the Commission, in collaboration with MSs, is committed to designing and promoting national agricultural advisory services to build up farmers’ capacity to adopt less polluting agricultural practices.

Finally, it highlights that attaining EU zero pollution targets will require finding synergies with the Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability (EC, 2020a) and the Circular Economy Action Plan (EC, 2020e), which also fall under the EGD umbrella. The former aims at shielding the environment from the most hazardous chemicals, whereas the latter calls for the replacement of mineral fertilizers with organics ones on farms.

The EU Climate Law (Regulation 2021/1119) sets out a framework for the progressive reduction of greenhouses gas emissions stemming from human activities and for the development and improvement of existing carbon sinks. The main goal is to reach climate neutrality by 2050.

To steer the EU towards the achievement of such an ambitious objective, the Law establishes a domestic reduction of net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030. As outlined above, two complementary courses of action have been devised and endorsed to undertake this transition. First, all EU policies must be implemented in a synergistic fashion to curb anthropogenic greenhouses gas emissions. Secondly, natural sinks must be conserved and enhanced to support carbon removals efforts.

Art.4 states that the Commission shall consider “the need to maintain, manage and enhance natural sinks in the long term and protect and restore biodiversity”. In particular, it acknowledges that agriculture, forestry, and land use sectors can significantly contribute to improving and restoring some critical natural carbon sinks. Art.5 argues that MSs shall step up their commitment to increase their capacity to adapt to climate change.

Soil constitutes the Earth’s largest carbon store. Scientific evidence indicates that carbon stored in it may be at least twice as high as that stored in the atmosphere and three times higher than that stored in vegetation. Sustainable soil management practices further enhance its capacity to sequester atmospheric carbon and increase, as a result, the overall amount of soil organic carbon (SOC) present in it; SOC is broadly defined as a key indicator of soil quality.

Thus, agroecological practices, healthy soils, and carbon sequestration feed into each other creating a virtuous cycle, a win-win solution, which has a huge positive impact on the provision of ecosystem services and on the offsetting of anthropogenic emissions. The report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on climate change and land stresses that soils rich in SOC represent one of the most effective solutions to adapt to climate change (Jia et al, 2019; Heuser and Itey, 2022).

What emerges from this analysis is that soil health, even though the text makes no specific reference to it, must be considered as one of the core elements of the EU Climate Law in order for it to be successful.

In this context, it is worth mentioning that the objectives of the EU Climate Law are backed by the EU Regulation 2018/841 (Regulation 2018/841) on the inclusion of greenhouse gases and removals from Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) in the 2030 climate and energy framework. The LULUCF Regulation, which is not part of the EU Green Deal, has the objective of attaining 310 Mt of CO2-equivalent net removals in the LULUCF sector by 2030 at EU level. In addition, MSs must ensure that emissions stemming from different land uses (e.g., cropland, grassland, wetland), as well as forested and deforested land, do not exceed greenhouse gas removals. Therefore, the same reasoning as for the European Climate Act applies here; although soil protection is not the main goal of this policy, LULUFC targets might promote sustainable soil management practices.

The EU Soil Strategy (EC, 2021e) gives a comprehensive overview of soil functions and challenges and outlines some pivotal actions that could improve its health. We will not dwell on the parts of the text dealing with soil monitoring, sustainable soil management, and soil contamination, as these form the backbone of the new Soil Monitoring Law proposal, which will be analysed in greater detail later on.

The Strategy emphasizes the importance of the wide range of ecosystem services provided by soil. It illustrates how healthy soils contribute to mitigating and adapting to the risks brought about by the climate crisis (e.g. flooding and droughts), obtaining suitable water resources, recycling nutrients, absorbing carbon from the atmosphere, preserving biodiversity, and preventing and reversing desertification.

In light of the increased awareness of the exceptional role play by this unique natural resource, the Strategy rightly indicates and tacitly criticises the fact that the EU has not yet granted it the same level of protection as water and air.

The vision laid down in this document is for all EU soil ecosystems to be in healthy and therefore more resilient condition by 2050. To this end, soil protection, sustainable management, and restoration must become the norm.

The objectives outlined in the Strategy include:

Restore degraded and carbon-rich ecosystems, reduce the drainage of wetlands and organic soils, and improve the conditions of drained and managed peatlands.

Combat desertification and soil pollution.

Achieve no net land take by 2050, thus drastically diminishing soil sealing.

Promote the “TEST YOUR SOIL FOR FREE” initiative to allow farmers to better understand the characteristics of their farms and encourage them to adopt best management practices.

Increase research and innovation to further enhance soil stewardship.

Expand soil literacy and stimulate the exchange of knowledge and best practices.

In the Soil Strategy reviewed earlier, the European Commission (EC) announced that it would develop a Soil Health Law to fill the legal vacuum left in this area and take all the necessary measures to protect and restore this resource. The proposal for a Soil Monitoring Law (EC, 2023a) serves as the first step towards fulfilling this commitment. It was adopted by the EC in July 2023. Thus, some of the measures in it could be amended, as the text has to go through the full legislative cycle before being approved.

In the EU Soil Strategy 2030, published in 2021, the European Commission (EC) announced that it would develop a “Soil Health Law” to take all necessary measures to protect and restore this resource. The proposal is now titled “Soil Monitoring and Resilience” (Soil Monitoring Law). This name change is well reflected in the content of the proposal and indicates that its main focus has shifted from soil health to soil monitoring.

The choice of a legislative rather than non-legislative approach was made in an attempt to establish a more legally sound framework for achieving healthy soils in the EU by 2050. A Directive determines a set of specific outcomes to be achieved but leaves it up to the MSs to design the measures they deem most appropriate to that end, in other words to decide how to transpose the directive into national laws.

The Commission has opted for a staged approach.

In the first stage, the goal will be to create a robust and consistent soil monitoring framework across Europe to describe the current state of soil health, addressing the current lack of adequate information. In this phase, MSs will need to assess the status of their soils through measurements taken within specific soil districts and then define which management strategies could lead to healthy soils by 2050. The Proposal sets also the objective to identify, investigate and carry out the risk assessment and management of potentially contaminated sites.

The establishment of a comprehensive soil monitoring framework is an important step forward as it will enable MSs to develop more effective intervention strategies to improve soil health and tailor them to specific geographic contexts. However, it is worth pointing out that the proposal includes no legally binding targets and/or measures to be adopted by MSs. The text states that the law is “designed to create the conditions for action to manage soils sustainably and to tackle the costs of soil degradation” (EC, 2023a, p10) and that it “does not require MSs to create any new programmes of measures or soil health plans” (EC, 2023a, p13).

In the second stage, six years after the entry into force of the law, the EC will review progress and decide whether stricter standards are needed to restore soils to healthy conditions by 2050.

The proposal is divided into seven chapters and an equal number of annexes. Its backbone can be outlined through the following five key components:

definition of soil health and establishment of soil districts,

monitoring of soil health,

sustainable soil management,

identification, registration, investigation, and assessment of contaminated sites,

restoration (regeneration) of soil health and remediation of contaminated sites.

Annex I comprises a set of soil descriptors and criteria that all soils must satisfy to be considered healthy. They are divided into three groups: Part A, Part B, and Part C. The first group (Part A) includes soil descriptors with criteria for healthy soil condition established at Union Level, the second group (Part B) includes soil descriptors with criteria for healthy soil condition established at MSs level, and the third group (Part C) covers soil descriptors without criteria. The Proposal establishes a “one-out-all-out” system, that is to say that soils must fulfil all indicators listed in Annex I to be considered healthy.

Annex II defines the methodology for determining sampling points.

The proposal also calls on MSs to define a set of sustainable soil management practices and proposes some in Annex III (e.g. avoid leaving soil bare by establishing and maintaining vegetative soil cover, especially during environmentally sensitive periods). However, MSs are not required to indicate a set of practices that must be observed, nor does it establish a set of practices to be restricted or prohibited.

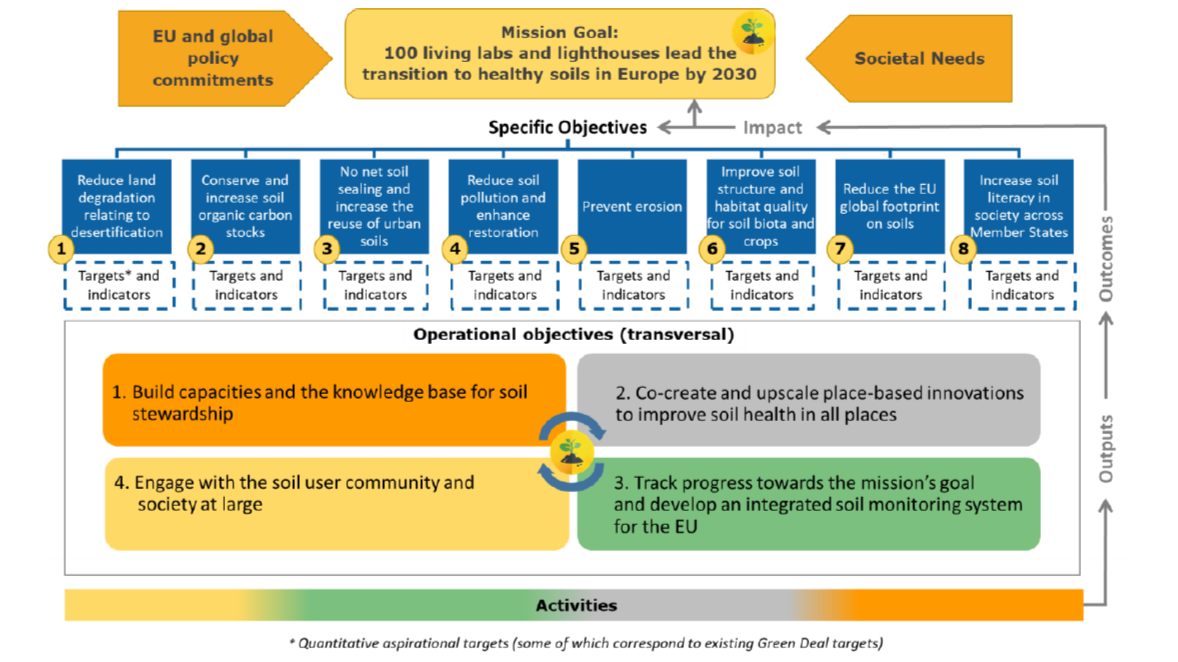

A “Soil Deal for Europe” is one of the five Research and Innovation missions of the Horizon Europe Programme that the Commission launched in September 2021. These missions recognize the need to promote cross-cutting and integrated strategies to address some of Europe’s most pressing societal challenges, and restoring soil health is considered one of them. They also seek to advance participatory and democratic approaches by putting citizens and stakeholders at the centre of the innovation process; the objective is to involve them in the design and implementation of effective and context-based solutions to achieve several critical European Deal targets (Panagos et al., 2022; EC 2021f).

The EC provides some data to explain why a mission dedicated to soil protection and restoration is critical to ensuring the continued existence of life on this planet. The EC argues that soil provides 95 percent of our food, as well as other vital essential ecosystem services such as biodiversity and climate regulation. At the same time, about 25 percent of soils in southern, central, and eastern Europe are subject to desertification processes, and between 60-70 percent of European soils do not meet soil health standards. Finally, the costs associated with the degradation of this resource are estimated at more than 50 billion euros per year in Europe alone (EC, 2021g).

The objectives of the mission are to lead a transition in Europe towards sustainable soil management and restoration, establish a holistic soil monitoring framework, and increase soil literacy.

The implementation will be carried out through the establishment of a network of one-hundred living labs and lighthouses in rural and urban areas. Living labs are defined as “user-centred, place-based and transdisciplinary research and innovation ecosystems” which will boost collaboration among ten to twenty individual sites, such as farms, forests, industrial settings etc, to co-create knowledge and innovations. Lighthouses, on the other hand, are defined as “as key places for demonstration of solutions, training and communication that are exemplary in their performance in terms of soil health improvement”; in other words, they are individual sites that stand out for their performance (EC, 2022a).

The mission’s momentum and impact can be further enhanced by exploiting synergies with other EU policies and initiatives. The coordination of activities under this mission, the EU Soil Strategy, and the EU Soil Observatory (EUSO) would help support data collection efforts for soil monitoring purposes and develop a comprehensive framework to address soil degradation and promote land stewardship.

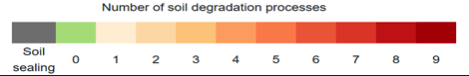

The European Soil Observatory (EUSO)EC, https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/eu-soil-observatory-euso_en) was launched in December 2020 to encourage and accelerate the creation of a coherent soil monitoring system for the EU. It was conceived and designed to become the most important repository of all soil-related data and knowledge generated in member countries.

One of the mains tools that has been developed within the EUSO framework is the Soil Health Dashboard. The latter provides EU-wide harmonised data on the current state of soils and highlights the main challenges they face. The following is the list of twenty-one indicators of degradation processes against which soil health is assessed: water erosion; wind erosion; tillage erosion; harvest erosion; copper concentration; mercury concentration; nitrogen surplus; phosphorus deficiency; phosphorus excess; soil organic carbon; soil biodiversity; soil compaction; soil salinization; soil sealing; peatland degradation; fire erosion; zinc erosion.

A map of Europe indicates which territories are affected by some of these processes. A coloured bar ranging from zero to nine is used to illustrate the level of soil degradation, where zero (green) means that the soil does not exceed any degradation threshold and 9 (red) means that it exceeds multiple thresholds. The Dashboard grants easy access to substantial and complex information, facilitating the evaluation of soil policy implementation.

EUSO complements and builds on the operational legacy of the existing European Soil Data Center (ESDAC), which has been Europe’s leading soil data repository since 2006. The goal is to enhance its capacity, support innovative data streams, and further harmonize national soil monitoring systems with EU monitoring programs. The most important EU monitoring Programme is known as Land Use/Cover Area frame statistical Survey (LUCAS). Since 2006, every three years the Statistical Office of the European Union (EUROSTAT) collects, in-situ, harmonised statistics on land use and land cover across the EU through a comprehensive survey which consider also soil parameters. LUCAS uses a standardised survey methodology for soil sampling, classifications, and data collection processes to generate consistent information on land use and land cover. Until 2020, more than 1,350,000 observations were collected in 651,780 different locations for 117 variables and 5.4 million photos. (D’Andrimont et al., 2020)

In addition, the Observatory will develop a robust engagement strategy to provide and receive support from EU research and innovation initiatives, particularly the EU Mission “A Soil Deal for Europe”. The Observatory will be the repository of final research outputs and thus benefit from research activities carried out, for example, in living labs and lighthouses. Meanwhile, it will steer future research by identifying and reporting gaps and knowledge needs.

In conclusion, EUSO aims to contribute to the achievement of the EU Green Deal’s soil-related targets and objectives by regularly providing monitoring information and indicators to relevant stakeholders. This will, on the one hand, foster and streamline the formulation of sound and evidence-based policies and, on the other hand, make it easier to evaluate policies that affect soil and hold policy-makers accountable for them. Finally, raising public awareness of these issues through the organization of European Soil Forums represents an additional benefit derived from EUSO. (Montanarella and Panagos, 2021; Panagos et al., 2022)

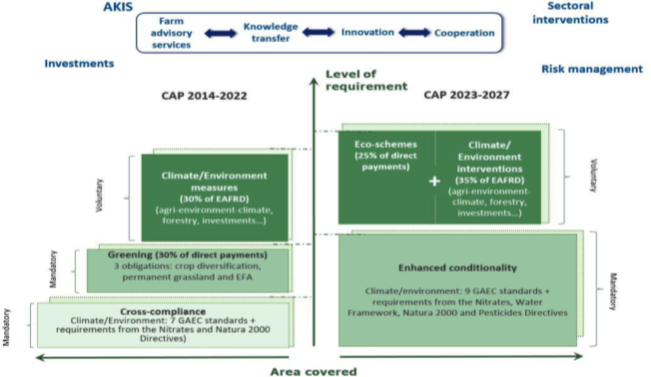

The CAP reform came into effect in 2023 and its duration will extend until 2027 (Regulation 2021/2115; Regulation 2021/2116; Regulation 2021/2117). Every year about 33 percent of the total EU budget (55.71 billion euros) is allocated to this policy, making it the most financially significant budget component (EP, 2023). This simple statistic demonstrates the great potential of this policy to support the environmental goals set by the European Green Deal and to drive a far-reaching transition towards a sustainable agricultural system in the region. However, the CAP has often been criticized in the past for not being sufficiently ambitious, especially with regard to the protection of natural resources (Guyomard et al., 2023; Pe’er and Lakner, 2020). This report aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the measures under the CAP without engaging in a critical analysis of it, which will be done in the next phase of project activities.

| EU Specific Objective | Impact indicators | Result indicators |

| (d) To contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation, including by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and enhancing carbon sequestration, as well as to promote sustainable energy. | I.11 Enhancing carbon sequestration: Soil organic carbon in agricultural land | R.14PR – Carbon storage in soils and biomass: Share of utilised agricultural area (UAA) under supported commitments to reduce emissions or to maintain or enhance carbon storage (including permanent grassland, permanent crops with permanent green cover, agricultural land in wetland and peatland). |

| (e) To foster sustainable development and efficient management of natural resources such as water, soil, and air, including by reducing chemical dependency. | I.13 Reducing soil erosion: Percentage of agricultural land in moderate and severe soil erosion. I.18 Sustainable and reduced use of pesticides: Risks, use and impacts of pesticides. | R.19PR – Improving and protecting soils: Share of utilised agricultural area (UAA) under supported commitments beneficial for soil management to improve soil quality and biota (such as reducing tillage, soil cover with crops, crop rotation included with leguminous crops). R.22PR – Sustainable nutrient management: Share of utilised agricultural area (UAA) under supported commitments related to improved nutrient management. R.24PR – Sustainable and reduced use of pesticides: Share of utilised agricultural area (UAA) under supported specific commitments which lead to a sustainable use of pesticides in order to reduce risks and impacts of pesticides such as pesticides leakage. |

| (f) To contribute to halting and reversing biodiversity loss, enhance ecosystem services and preserve habitats and landscapes. | I.21 Enhancing provision of ecosystem services: Share of agricultural land covered with landscape features. I.22 Increasing agro-biodiversity in farming system: Crop diversity. | R.29PR – Development of organic agriculture: Share of utilised agricultural area (UAA) supported by the CAP for organic farming, with a split between maintenance and conversion. R.30PR – Supporting sustainable forest management: Share of forest land under commitments to support forest protection and management of ecosystem services. R.34PR – Preserving landscape features: Share of utilised agricultural area (UAA) under supported commitments for managing landscape features, including hedgerows and trees. |

|

Areas |

Main Issue |

Requirements and standards |

|

|

Climate and Environment

|

Climate change (mitigation of and adaptation to)

|

GAEC 1

|

Maintenance of permanent grassland based on a ratio of permanent grassland in relation to agricultural area at national, regional, sub regional, group-of-holdings or holding level in comparison to the reference year 2018.

Maximum decrease of 5 percent compared to the reference year. |

|

GAEC 2 |

Protection of wetland and peatland.

|

||

|

GAEC 3

|

Ban on burning arable stubble, except for plant health reasons. |

||

|

|

Soil (Protection and quality)

|

GAEC 5

|

Tillage management, reducing the risk of soil degradation and erosion, including consideration of the slope gradient.

|

|

GAEC 6 |

Minimum soil cover to avoid bare soil in periods that are most sensitive.

|

||

|

GAEC 7 |

Crop rotation in arable land, except for crops growing under water.

|

||

At the end of June 2023, the EC published a document in which it provides an overview of the 28 approved CAP Strategic Plans, highlighting the most important elements underlying the implementation of this policy (EC, 2023c). The tables and figures present in this document will be particularly useful to illustrate the strategies and definitions adopted by MSs to implement CAP measures in their territories. For the purpose of this report, we will analyse the decisions made by MS on measures potentially targeting and affecting soil health, especially GAECs and eco-schemes.

GAEC 1 states that MSs must maintain the 2018 ratio of permanent grassland in relation to agricultural area at national, regional, sub-regional, group-of-holdings or holding level. However, it is stipulated that this ratio may decrease by a maximum of 5 percent. This is the only GAEC standard that sets a clear target that all MSs must meet.

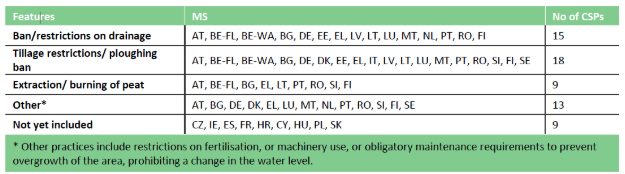

GAEC 2 focuses on the protection of carbon-rich soils, namely wetlands and peatlands. MSs are allowed to delay its implementation to 2024 or 2025, but this decision can only be justified by arguing that agricultural areas qualified as wetlands and peatlands have still to be properly mapped.

16 MSs used this justification to postpone implementation (BG, CZ, EE, IE, ES, FR, HR, CY, LV, LT, HU, PL, PT, SI, SE, SK), while 5 chose a two-step phased approach, meaning that a first set of rules will be enforced from 2023 and the others from 2024/2025 (BE-FL, DE, EL, NL, FI). In Germany, the only regions which adopted such a phased approach are Lower Saxony, Hamburg, Bremen, and Saarland.

This GAEC requires MSs to define and enforce land management practices which eliminate or reduce the amount of carbon released in the atmosphere. The majority of MSs have established management practices related to: ban/restrictions on drainage; tillage restrictions/ploughing ban; extraction/burning of peat.

GAEC 5 demands MSs to introduce specific soil tillage requirements to minimise the risk of soil degradation and erosion. The requirements will have to be enforced in areas particularly affected by these phenomena, especially considering slope gradients as a key criterion of vulnerability and risk.

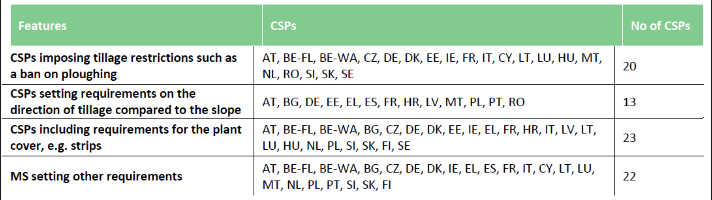

The main land management practices designed and imposed by MSs can be grouped into three distinct but potentially overlapping categories: restrictions on tillage, such as prohibition of ploughing, requirements on the direction of tillage relative to the slope, and requirements on the use of vegetation cover in particular areas or times of the year.

GAEC 6 aims at protecting soils by reducing the negative impact of erosion and loss of soil organic matter during the most sensitive and potentially hazardous times of the year.

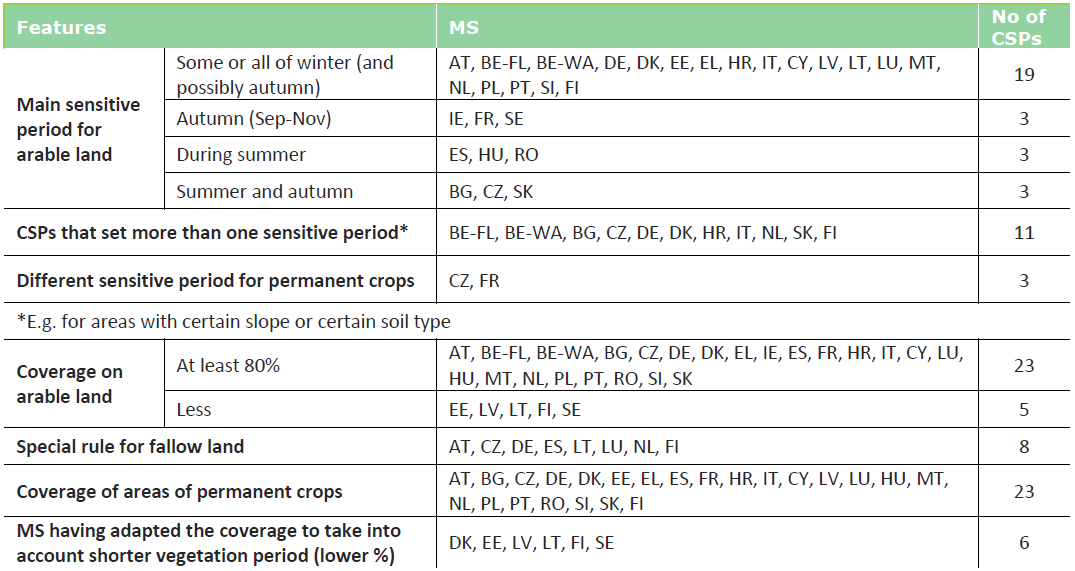

The definition of what constitutes a “sensitive period” and the percentage of arable land this GAEC applies to are two key elements to assess national GAEC 6 standards. Most MSs chose autumn and winter as the most sensitive periods, while some paid more attention to the summer season. With regard to the area covered by this standard, 23 MSs will apply soil cover requirements to more than 80 percent of their arable land. This percentage decreases significantly in some northern countries that have had to adapt the standard to their particular climatic conditions and different growing seasons.

The following is a list of practices that MSs have generally endorsed and which farmers can adopt to guarantee soil cover: sowing crops/catch crops/winter crops, leaving the stubble, or crop residues on the land or by mulching.

GAEC 7 intends to provide important benefits to all dimensions of soil health as crop rotation can improve productivity, increase the amount of soil organic carbon, break the biological cycle of pests and diseases, and enhance soil water retention capacity.

The majority of MSs have translated this GAEC into a standard focusing exclusively on crop rotation, determining that it will take place annually on considerable share of arable land at holding level. All plans stipulated that the change of the main crop must occur after three years at the latest. Finally, almost all plans made use of the exemptions envisaged for this GAEC related to farmers with less than 10 ha of arable land and holding with more than 75 percent of temporary or permanent grassland.

Organic farmers are automatically exempted from the requirements stemming from this standard as it is assumed that they already fulfil it.

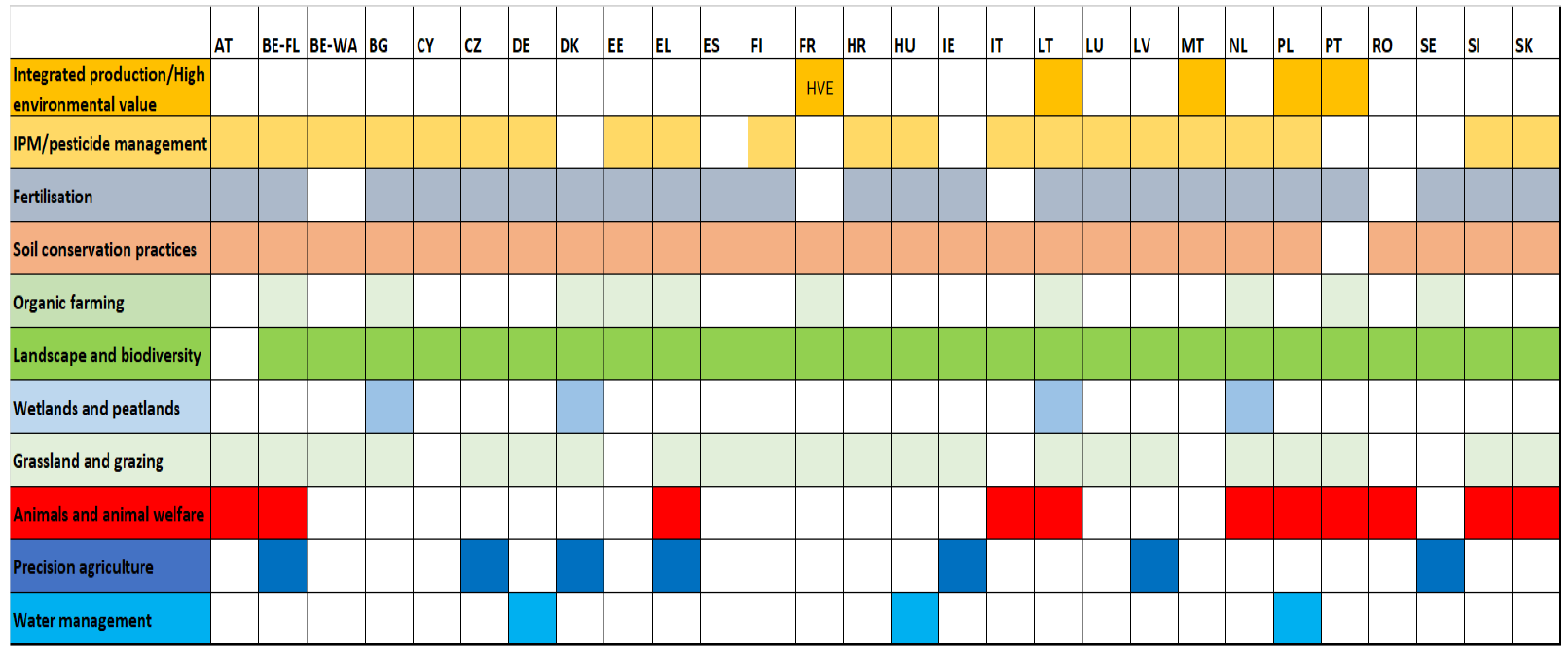

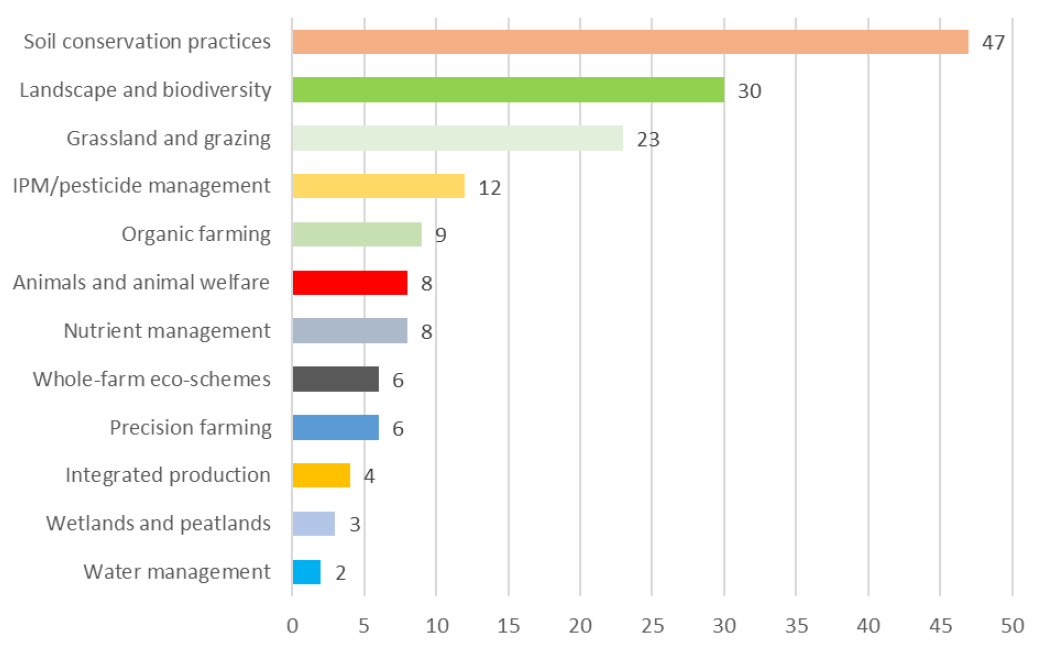

In terms of Eco-Schemes, the Commission’s overview of CAP Strategic Plans does not provide detailed data. However, what clearly stands out from the available information is that MSs have decided to pay special attention to soil conservation during the formulation of their eco-schemes. As illustrated by the two following tables, eco-schemes addressing soil conservation practices account for 30 percent of all eco-schemes, and only Portugal has not included one in its Strategic Plan. In other words, it appears that this new tool available under Pillar I might significantly support management systems that enhance soil health. These are some of the common practices associated with eco-schemes: long-cycle rotations, leguminous crops planting, crop diversification, tillage restrictions (e.g. no-till), catch crops, green cover in permanent crops, are straw incorporation.

In addition to those strictly related to soil conservation, eco-schemes which support integrated pest management practices (e.g. biological control, use of resistant local species and varieties etc.), nutrient management practices (e.g. elimination of mineral fertilizers, use of organic fertilizers etc.), and organic farming have received great attention.

The Directive (Directive 2004/35) creates a European an environmental liability framework which applies and enforces the “polluter-pays” principle with the goal of preventing and remedying environmental damage. In other words, it aims to hold liable operators whose occupational activities (e.g., waste management operations) have already caused damage to protected species and natural habitats or pose an imminent threat of such damage.

The operator must take preventive measures when there is an imminent threat of environmental damage. In addition, the same actor must take remedial measures when such damage has already materialized as a result of his/her operational activities. The Directive establishes three types of remediation:

Primary remediation consists of remedial measures that restore damages natural resources to their original state.

Complementary remediation consists of remedial measures put in place when the damaged natural resources cannot be fully restored through primary remediation.

Compensatory remediation requires the operator who has caused environmental damage to compensate for the interim losses that incurred from the day the damage occurred till the day the natural resource in question has been fully restored to its baseline condition.

Annex II of the Directive, entitled “Remedying of Environmental Damage”, deals specifically with the remediation of land damage. It states that all necessary measures have to be taken to guarantee that all relevant contaminants are removed, controlled, contained, or diminished. The objective is to ensure that the land does not pose a danger to human health.

The IED Directive (Directive 2010/75) was established with the aim of controlling and regulating pollutant emissions from industrial installations. It adopts and applies the “polluter-pays” principle and the principle of pollution prevention in the attempt to prevent, curb, and phase out pollution to the greatest possible extent.

It promotes an integrated approach to pollution prevention and control. It argues that addressing soil, water and air pollution separately risks creating legal loopholes which allow operators to shift environmental pollution from one natural resource to the another. Therefore, to ensure the protection of the environment as a whole, it is necessary to adopt an integrated approach which can prevent and reduce the amount of emissions into soil, water, and air.

Each installation should be able to operate only if it has a permit that assigns specific responsibilities to its operator. As a basis, each permit should encompass all measures necessary to achieve a high level of protection of the environment as a whole. In particular, permit conditions should include appropriate requirements for the regular maintenance and surveillance of those measures designed to prevent emissions to soil and groundwater resources. Moreover, it calls for the inclusion of requirements for the regular monitoring of these natural resources to assess the level of hazardous substances in them.

Finally, once activities at the site have ceased, the operator must evaluate the extent to which soil and groundwater resources are contaminated by the hazardous substances used, produced, or released by the installation. If the installation has significantly and negatively altered the status of these resources compared to the baseline data collected prior to the start of activities, the operator will have to take all necessary measures to redress the situation and restore the site to its original conditions.

The Directive (Directive 2008/98) sets out measures to protect the environment and human health by preventing and reducing the generation of waste, the negative impacts that can be generated through waste management and resource use. In addition to the polluter-pays principle, it introduces the “extended producer responsibility”.

Art. 13 stipulates that waste management operations have to be carried out without endangering the environment as a whole and, in particular, without posing a risk to water, air, soil, plants or animals.

The Directive (Directive 1999/31) lays down technical requirements for the functioning of landfill sites to protect human health and the environment. In particular, it aims to prevent and/or reduce the harmful impact that landfills might have on surface water, groundwater, soil, and air by establishing where they should be situated and how they should be designed. It also assigns specific responsibilities to the operator in the period following the closure of a landfill. The operator must notify the competent authorities if serious environmental damage has occurred at the site and, if it has, he/she will be responsible for monitoring the landfill and undertaking the corrective measures specified by the authorities.

Annex I states that in order to minimise and eliminate soil pollution, a combination of a geological barrier and bottom liner should be implemented during the active operational phase and during the post closure phase of the landfill.

Promoting the transition to a more circular economy is a key principle of this policy.

The WFD (Directive 2000/60) constitutes the main piece of legislation designed to safeguard water resources in Europe. It covers all types of water, from groundwater to surface water, and from inland to coastal waters. Its primary goal is to abate the emission, leakage, and discharge of hazardous substances to waters in order to protect and enhance the quality of aquatic ecosystems.

Agricultural activities can have a huge detrimental impact on water quality due to, for example, the inefficient management and use of fertilizers (Evans et al., 2019). Disproportionate amounts of nitrogen in agricultural soils can provoke surface and groundwater contamination through runoff and leaching, possibly leading to water eutrophication and acidification (Mancuso et al., 2021). Poor agricultural practices resulting in nutrient and pesticide loads do also threaten soil health as they constitute some of the major causes of soil biodiversity loss and soil contamination (Frelih-Larsen and Bowyer, 2022). Thus, although the Directive does not expressly mention and address soil protection, the achievement of its goals is highly dependent on the promotion and implementation of sustainable soil management practices that benefit soil health.

This Directive (91/676) precedes in time and constitutes an essential part of the overall framework established by the WFD. It spells out what is implicit in the WFD, in other words it describes and addresses the negative impact of nitrates deriving from agricultural sources on water quality. As previously pointed out, the excessive use of nitrogen-containing fertilizers is a considerable source of pollution that endangers both human health and aquatic ecosystems. Therefore, preventing and reducing this form of pollution is the primary objective of the Directive under analysis, along with promoting the use of good farming practices.

Art.3 stipulates that MSs must designate Nitrogen Vulnerable Zones (NVZs), which are all known areas in their territories that drain into polluted waters or water at risk of pollution and which contribute to nitrogen pollution.

Art.4 provides that MSs must create a code or codes of good agricultural practice that farmers can decide to implement on a voluntary basis. Such codes should contain some provisions covering items listed in Annex II, the following are some examples:

periods when the land application of fertilizer is inappropriate;

the land application of fertilizer to steeply sloping ground;

the conditions for land application of fertilizer near water courses;

the maintenance of a minimum quantity of vegetation cover during (rainy) periods;

land use management, including the use of crop rotation systems.

Art.5 states that MSs must establish action programmes for designated NVZs, which will have to include the mandatory measures laid down in Annex III. Here are a few examples:

measures already included in Codes of Good Agricultural Practice that become mandatory in NVZs;

measures that guarantee that the overall amount of livestock manure applied to a particular land each year does not exceed a specific amount per hectare. In areas which are already affected by nitrogen pollution, the maximum amount of nitrogen from manure that can be applied annually is 170 kg/ha;

measures limiting the land application of fertilizers, considering soil conditions, soil types, land uses, crop needs etc.

Therefore, the same reasoning made for the WFD applies in this case. The Directive does not explicitly focus on soil health, but the measures it promotes to achieve its objective will undoubtedly benefit soil health by reducing soil contamination, enhancing soil organic matter, and supporting soil biodiversity.

The Directive (86/278) aims to regulate the use of sewage sludge in agriculture to prevent and reduce adverse impacts on soil, vegetation, animals, and man and to promote its proper use. To this end, it sets limits for the concentration of seven heavy metals (cadmium, copper, nickel, lead, zinc, mercury, chromium) in soils to which sludge is applied and in sewage sludge intended for agricultural use. The use of sludge is prohibited both in soils where the concentration of heavy metals already exceeds maximum values and in soils that would exceed the same values if sludge ware applied; these values are set out in Annex I. Art. 7 specifies that MSs must ban the use of sludge on:

on soil in which fruit and vegetable crops are grown, except for fruit trees;

on grassland or forage land that will be grazed by animals or harvested in the next three weeks;

on ground intended for the cultivation of fruit and vegetable crops which are normally in direct contact with the soil and normally eaten raw, for a period of 10 months preceding the harvest of the crops and during the harvest itself.

In addition, the directive requires that sludge be used according to the nutritional needs of plants and that it not compromises soil quality or surface and groundwater quality.

The Directive (Directive 2009/128) is designed to achieve the sustainable use of pesticides throughout the EU. To this end, it aims to reduce the harmful effects of pesticides on human health and the environment and to stimulate the uptake of integrate pest management (IPM) practices and principles and the use of non-chemical alternatives. According to the document, each MS is required to adopt a National Action Plan to define its objectives, the measures to be applied, and a timetable for their implementation. It is the responsibility of MSs to ensure that all professional users, distributors, and advisors have access to trainings provided by designated competent authorities that enable them to receive adequate and up-to-date knowledge; training subjects are listed in Annex I. Aerial spraying is generally prohibited since it can provoke significant detrimental impacts on the environment; however, some exemptions are specified by art.9. Finally, the Directive encourages MSs to set up appropriate measure to promote IPM and to outline in their National Action Plan how they intend to boost its principles. Annex III describes general principles of IPM.

According to the European Court of Auditors, limited progress has been achieved so far on measuring and effectively reducing pesticides risks and impacts in the EU. Furthermore, the Farm to Fork and Biodiversity Strategy’s targets on pesticide reduction are not yet integrated in this directive (European Court of Auditors, 2020). For these reasons, in June 2022, the European Commission presented a proposal for a new Regulation on the Sustainable Use of Plant Protection Products (EC, 2022). The proposal, being a Regulation, would be binding and uniformly applicable to all MSs. The main objective pursued by the Commission is to revise the existing legislation to align it with the goals set out by the EU Green Deal, especially the Biodiversity and Farm to Fork Strategies. This means that, if passed, it would aim to further counter the adverse effects of pesticides on natural resources and biodiversity by:

The Regulation (2019/1009) expands the range of fertilizer products covered by the harmonization rules to facilitate the trade of organic and recovered fertilizers. Replacing and repealing Regulation 2003/2003, which focused almost exclusively on inorganic and chemical fertilizers, it paves the way for the following products to be marketed in the EU single market: organic and organo-mineral fertilizers, soil improvers, inhibitors, plant bio-stimulants, growing media, liming materials, and fertilising product blends.

All CE-marked fertilizer products will have to comply with a number of safety and quality standards, such as maximum levels of contaminants and pathogens (disease-causing microorganisms) and minimum nutrient content. Setting maximum values for toxic contaminants could, on the whole, promote soil protection at the European level. However, it is crucial to emphasize that the standards set by this regulation will affect stakeholders involved in the design, production, and trade of fertilizer products rather than farmers, as it does not provide standards or guidelines on how such products should be applied. Furthermore, it does not affect products that do not bear the CE mark; in other words, harmonization remains optional, non-harmonized fertilizer products can be made available on the internal market in accordance with national laws and general free movement rules.

The Directive (Directive 2007/60) is designed to limit and manage the hazards and risks to the environment and human health produced by floods. MSs are required to carry out flood risk assessments, identify vulnerable areas, and create flood hazard and flood risk maps. According to the data emerging from these maps, they must set up adequate flood risk management plans and measure to deal with these events.

Although the document does not mention or explicitly refer to soil protection, there are several ways in which it could potentially benefit soil health. For example, the text states that floods are natural phenomena that cannot be controlled by humans, yet acknowledges that human activities could contribute to their likelihood and negative impacts. Soil sealing caused by increasing urbanization, such as by human settlements and economic activities, of floodplains and riparian lands reduces the water retention and infiltration capacity of the soil and generates increased risks of floods. Consequently, some of the measures that could be implemented to effectively prevent and address these phenomena require society to work in harmony with nature rather than against it. Support for green infrastructure could be a win-win solution for flood risk reduction and management and soil protection (Frelih-Larsen and Bowyer, 2022).

Habitats (Directive 92/43) and Birds (Directive 2009/147) Directives are the two most important pieces of EU legislation that establish a robust framework for the protection and conservation of vulnerable and threatened biodiversity. Together, these two policies cover a wide range of species and habitat types that not only need to be adequately safeguarded but also restored to a favourable conservation status to allow them to thrive.

The Habitats Directive provides for the establishment of a European ecological network of special areas of conservation for the maintenance of natural habitats and the protection of wild fauna and flora within the EU, called Natura 2000. This network is to include areas comprising the habitat types listed in Annex I and the habitats of species listed in Annex II. The directive mandates each MS to establish and promote a national register of Natura 2000 sites, for which specific and appropriate conservation measures and management plans must be designed and implemented to ensure the preservation of their long-term positive environmental status.

The directives do not explicitly deal with soil protection. However, they cover areas considered environmentally vulnerable and of community importance, such as grasslands, forests, and wetlands. Measures taken to safeguard and restore these areas tend to address most forms of environmental degradation, thereby generating direct positive or spillover effects on soil protection and soil biodiversity (Heuser, 2022).

This report aimed to identify and examine the most relevant EU policies and support mechanisms that have a direct or indirect impact on soil health. We analysed strategies, action plans, directives and regulations, as well as research programmes and initiatives such as the EU Soil Mission and the EU Soil Observatory.

What emerges from this analysis is that the protection of soil health has to be realised through the implementation of diverse and varied policy instruments that often do not have soil health as a primary or secondary objective. At present, the preservation of this unique natural resource and the promotion of sustainable soil management practices are absolutely crucial for Member States to attain the objectives of policies focusing on air, water, habitats, population health, etc.

We also noticed that strategies and action plans are often quite progressive in terms of supporting soil health but have little impact due to their non-mandatory nature. On the other hand, several directives and regulations only indirectly affect soil health but can be more effective due to their mandatory nature.

It will now be crucial to follow the developments related to the proposal for a Soil Monitoring Law and to closely examine the European Commission’s forthcoming publication on how the CAP strategic plans drawn up by MSs can contribute to the achievement of CAP objectives.

In conclusion, this work lays a solid foundation for the next project activities, that is to say for the elaboration of the middle version of the policy navigator (D5.5). The latter will, indeed, require us to identify policy gaps, highlight potential synergies between policies and, most importantly, producing recommendations for the mid-term evaluations of the Soil Mission (2025), the EU Farm to Fork and Biodiversity Strategies and the current CAP (2023-2027).